blog: China-Taiwan: A(nother) looming crisis for the Electric Vehicle industry?

Friday 7th July 2023

As leaders around the world queue up to label the potential for a China-Taiwan crisis as, “the greatest threat to global security of the modern era”, or words to that effect, it seems slightly facile to ask, “so, what does that mean for the Electric Vehicle industry?”. And, of course, there are issues of far greater consequence to motivate parties on all sides to avoid a major escalation of current tensions over the Taiwan Strait. However, the Electric Vehicle (EV) industry’s chronic dependence on both countries (not just China or Taiwan) for its supply chain, I believe, makes it a uniquely interesting topic to consider, and one which perhaps hasn’t garnered the attention it deserves.

A market of growing significance

One topic not short of headlines is the growing influence of EVs on the automobile market. The share of electric cars in global new vehicle sales has more than tripled in the last three years, from around 4% in 2020 to 14% in 2022, with over 10 million electric cars sold in 2022. And it’s not just cars. Buses are the most electrified road segment, excluding two-/three-wheelers; over 3% of buses were electric in 2022 and, if policies are met, this is expected to rise to 10% by 2030, at 2.7 million electric buses (e-buses).

With governments around the world pursuing ambitious pledges of all-EV new vehicle sales in the next 10 to 15 years, the total global EV fleet is expected to grow to about 240 million vehicles by 2030.

This massive (and rapid) expansion of a currently fledgling market can only be pursued on the back of a reliable and, crucially, resilient supply chain.

China: EV trailblazers

China has marched ahead of practically all competition when it comes to EV and, in particular, EV battery production. A combination of healthy carrot and comprehensive stick policies, along with impressive foresight from the Chinese government, has meant that China leads the way both in terms of supply and demand for EVs, both producing and owning over half of the world’s EVs.

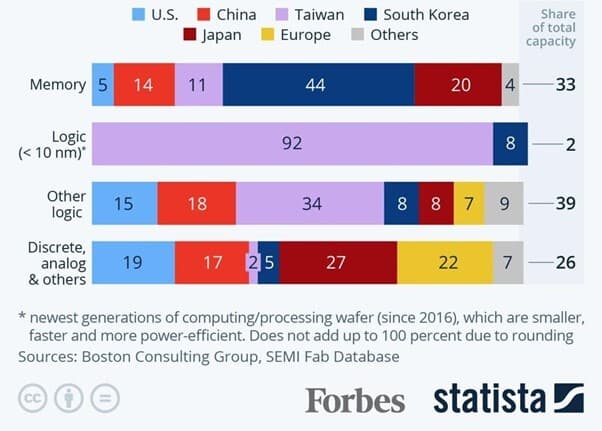

Enabling this is a firm grasp at every stage of the supply chain (shown by the dominance of red bars on the graph below; representing China). Upstream, China has more influence than it may appear at first, with Chinese companies owning 80% of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s cobalt mines. This influence extends right the way to the downstream segments; producing over 75% of all EV batteries. And in a fourth stage, hidden from the graph below, China also dominates the EV battery recycling space, with over 70% of the world’s capacity.

OK, so China dominates the EV supply chain. So what? China dominates lots of supply chains. Why should we be particularly concerned about the EV industry?

Well, overdependence on one supplier for pretty much all things EV leaves countries hoping to ramp up EV adoption in the near future, such as the UK, very vulnerable to any disruption to China’s supply. There are no alternative suppliers at present who can quickly expand existing production to pick up the slack, should China’s supply be largely or entirely taken off the market.

Again, this is the case for many industries. But the EV industry is particularly vulnerable specifically to a China-Taiwan crisis because of the second element of this equation; Taiwan.

Taiwan: punching above its weight

Just as China dominates the EV supply chain in general, so too does Taiwan dominate one very specific but crucial EV component; semiconductors.

Semiconductors (a.k.a. microchips or computer chips) are needed for electrical components in all vehicles, from simple indicators to far more complex infotainment systems and, increasingly, autonomous vehicles. As vehicles become more complicated, the greater the need for more advanced semiconductors.

This is where Taiwan comes in. Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s most complex semiconductors currently, and over 60% of all semiconductors in the world.

Crucially, EVs require roughly twice as many semiconductors as Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEVs), making them uniquely vulnerable to disruptions to Taiwan’s semiconductor supply.

So, there’s a double jeopardy when it comes to the EV industry and a China-Taiwan crisis. The EV industry is heavily reliant on China, and is also more reliant than the ICEV industry on Taiwan for semiconductors, and a crisis could drastically disrupt both countries’ supply in one go.

What does the future hold for China and Taiwan?

The truth is nobody knows. Predictions vary wildly in terms of when a crisis may occur and, indeed, if it might ever occur. Certainly, tensions are running high, with President Xi Jinping claiming he is willing to use force to “reunify” Taiwan, in his words, and intensifying military exercises around the island. The current party in power in Taiwan is pro-formal independence and its leader, Tsai Ing-wen, shows no signs of submitting to China’s demands; quite the opposite.

With that in mind, it's important not to underestimate the likelihood of a crisis over Taiwan, and to prepare for it accordingly.

So, what might a China-Taiwan crisis actually look like?

It would likely take one of two forms; a blockade or an invasion. Both would require the use of force, but a blockade would be far less risky and less costly and, hence, more likely. Although, it may be that a blockade is used as a forerunner for a full-scale invasion, to soften Taiwan up and gauge its allies’ reactions.

Either way, there would be significant ramifications for the EV industry, with both likely leading to;

- Increased lead times for materials, batteries, and microchips;

- Increased metal and battery prices;

- Limited imports and exports from/to China and Taiwan; and

- Potentially EV manufacturer exits from China.

An invasion would almost certainly result in more pronounced impacts than a blockade, particularly for the semiconductor industry, which could see highly valuable factories wiped out.

The severity and duration of the impacts would also largely be dependent upon Taiwan’s ability to defend and sustain itself, and the actions (or lack thereof) of its allies. These are both unclear, so it is hard to accurately predict the extent of the impacts of a crisis. However, it is hard to imagine a scenario in which a crisis does not significantly impact the EV industry’s supply, given its dependence on the two countries, at least in the short-term, if not the long-term.

So, what can be done?

If the UK wishes to continue down the path of mass EV adoption, and that is a big “if” (more on that later), then it should follow the current buzz-phrase being pedalled by political and industry leaders alike; “de-risk, not decouple”. Essentially, this points to reducing overdependence on China and Taiwan and, thus, exposure to a crisis, without completely severing ties with either country. That would be counterproductive; effectively self-imposing the impacts of a crisis without one occurring.

De-risking could, and should, take many forms. Taking the UK as an example, there are both trade and technological pathways, which can complement one another. And, whilst each country’s current EV context is unique, many of the options available to the UK could be applied around the world.

Diversifying supply chains

Perhaps the first option that springs to mind when considering reducing dependence on individual suppliers is diversifying the pool of suppliers. This naturally spreads the risk of any nation’s supply being disrupted and provides the platform for other nations to scale up supply should one nation’s production be taken out of the mix.

For the UK, there are two interconnected aspects to this approach:

- Bolstering domestic manufacturing capabilities

- Better facilitating international trade

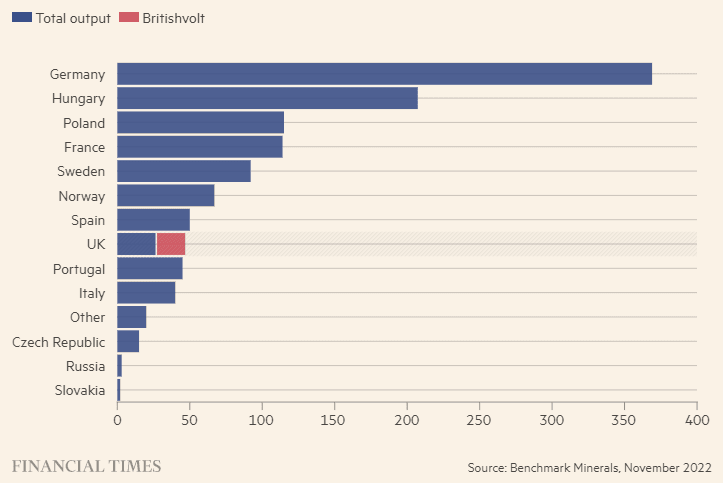

When it comes to domestic EV manufacturing capabilities, the UK is really lagging behind its counterparts. This is most strikingly demonstrated by the gigafactory race, in which the EU is taking leaps and bounds with over 30 gigafactories lined up, compared to the UK’s two (or possibly three).

There are some structural reasons for this, which will need to be addressed to lay the foundations for greater private investment in the UK’s gigafactory ambitions. Brexit tariffs and a lack of government financial support at an early stage in gigafactory developments have discouraged potential investors. Both of these issues will need to be addressed if the UK is to attract the investment it so desperately needs.

But even if that could be achieved, it would require strong international trade relations, and would only provide diversification of supply in the medium- to long-term. A China-Taiwan crisis may not afford that luxury of time. This places a particular importance on developing international trade relations in the short-term, to help diversify and bolster supply should it be required in the next few years.

South Korea provides the most credible option when it comes to batteries. Its “Big Three”, which includes LG and Samsung, make it the second largest battery producer after China. Moreover, they are currently excluded from US EV production due to the Inflation Reduction Act, providing a window of opportunity for the UK to strengthen ties with the electronics powerhouse with a major rival largely out of the picture.

However, trade with South Korea would still be threatened by a China-Taiwan crisis, with its exports currently passing through the Strait of Taiwan. It may be wise, then, to support countries with ambitions to develop their EV industries. India, in particular, holds huge potential, with growing domestic demand, a location largely shielded from a China-Taiwan crisis, and key players in the gigafactory market already, such as TATA.

Semiconductors have more limited options, given the advanced manufacturing capabilities required. The UK has already struck up a deal with Japan for Research & Development (R&D) in the semiconductor space; building on this deal to include mass orders of semiconductors provides the best opportunity to shore up its supply in the short-term.

Battery technologies

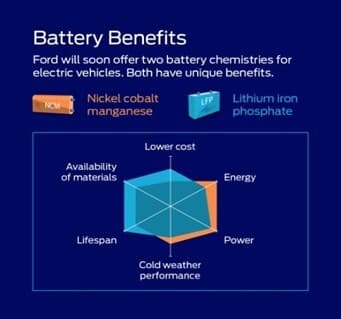

Looking to technological de-risking strategies, the composition of batteries holds some opportunities to reduce dependence on China. Lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries are a relatively uncommon technology currently due to their lower range than more typical batteries, which generally use cobalt to increase ranges. However, LFP ranges are improving, and their lack of cobalt means one less element to rely on China for.

However, LFP batteries are hardly a silver bullet as it stands. They may not rely on China for cobalt, but they are, at present, mostly produced by the EV giant. Supply of LFPs must be diversified first before this can represent an effective de-risking strategy.

Recycling

Recycling of EV batteries is perhaps the single most important challenge for the EV industry to overcome for it to be seriously considered a “sustainable” mobility solution. If batteries could be efficiently recycled, it could massively reduce the requirement for finite rare earth metals to be extracted and, if batteries could be recycled around the world, it could also diversify the supply of EV battery components.

The early signs are promising. Research has shown as much as 90% of lithium can be usefully recycled, which would almost make the EV battery industry circular if this could be translated to a commercial scale.

But there’s a catch. As you may recall, China dominates the EV battery recycling industry, with over 70% of the world’s capacity in this area. Again, other countries, including the UK, will need to increase their recycling capabilities for this to become a de-risking option. There’s a theme developing here…

A harder sell, but a better medicine?

As alluded to, that all assumes that the UK follows the expected mass EV adoption. But, given the challenges outlined, which aren’t exhaustive and aren’t limited to a China-Taiwan crisis, this surely is an opportunity to ask ourselves, “is this the path we really want to go down?”.

Simply replacing fossil fuels with electric batteries in our current fleet of vehicles does not hold the answer to many of our current mobility challenges and presents many more. The overdependence on private vehicles is at the heart of issues of congestion and demand for finite resources.

But, much like the overdependence on China and Taiwan, the answer lies not in decoupling from EVs; instead, reducing our dependence on them. EVs do bring many benefits compared to ICEVs and there is certainly a place for them in public transport and low levels of private vehicle use, where public transport is less feasible. However, to meaningfully combat issues such as congestion and demand for finite resources, greater adoption of public transport and active travel provides a far less risky and more sustainable future.

Of course, this comes with its own issues, not least a harder vision to sell politically. And it won’t happen on its own. Existing public transport and active travel networks will need to be grown to provide attractive and realistic alternatives to private vehicle use. The good news is the billions of pounds that might have been spent on trying to catch up in the EV race could be redirected for exactly that.

It’s not a simple solution, by any means, but a more effective one, perhaps.

If you'd like to read the entire paper as presented at TPM 2023 or any of our other papers please click here.